When you consider the countless hours Meg Williamson has spent analyzing literally thousands upon thousands of samples in the Plant and Pest Diagnostic Clinic, it’s easy to think of her as a consummate scientist.

She is, of course. But that’s far from all she is. Meg is also a teacher, and among the people who exemplify Clemson’s banner of “Regulation Through Education,” she has carried that banner around the world.

From the rice paddies of Cambodia to the homes and farms of South Carolinians seeking solutions to save their gardens, crops and yards, Meg has not only provided a diagnosis for the problems she’s been given, but has helped find solutions, too.

“I think she really enjoys teaching,” said Martha Froelich, a former Clemson graduate student who joined the clinic as an assistant diagnostician. “She’s got a wide range of experience, so she’s very knowledgeable. Meg taught me a lot about diagnosing diseases that I wasn’t working on as a grad student. That really broadened my range of knowledge.”

Land grant universities we established with a specific mission: To put knowledge to work. Williamson — a University of Tennessee alumna — accepted that mission early on. She also recruited teammates.

In any given year, dozens of Clemson faculty and Extension agents from a wide range of academic disciplines assist the Diagnostic Clinic by identifying diseases, insects or plants or by providing recommendations on how to manage them. The clinic also plays an essential role in the Department of Plant Industry’s mission to detect, identify and document new plant diseases and pests in South Carolina.

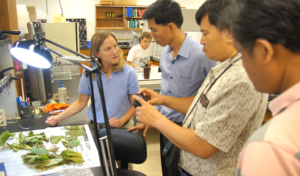

Williamson has routinely hosted delegations from around the nation and the world for tours and training sessions to help others adapt Clemson’s approach to meet their own needs. One of those has special meaning to Meg.

The July 2012 visit from three senior Cambodian agriculture officials came as an extension of a long-standing agreement with the United States through the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Williamson was one of a number of agriculture officials that USAID had sent to Cambodia — she made four trips in all — to help that country build its agricultural infrastructure and manage a diverse, widespread community of small farms.

“The Cambodians were just beginning to build some of the infrastructure they need to modernize agricultural production. They needed people to help train them,” Williamson said.

“It’s a challenge to adapt. They don’t have the resources that you expect in more developed countries, but the same principles apply,” she said. “The need for more efficient and safer food production is the same.”

The Cambodian visitors to Clemson’s Diagnostic Clinic eagerly studied the lab — not merely for the types of equipment and diagnostic techniques it used, but for the processes Williamson had in place.

“What we learn from what you do here, we can adapt to how we work with our farmers,” Heng Chhun Hy, deputy director of Cambodia’s Department of Plant Protection, said in touring Williamson’s lab. “In Cambodia we don’t yet have the equipment to match the function of this laboratory. But if we learn how this system works, we can use it in the future to improve our country, to build our country.”

After her career with Regulatory Services, it’s hard to say who has benefitted the most from Williamson’s work. South Carolina agriculture, certainly. Palmetto State gardeners and homeowners, too. In fact, farmers, gardeners and agriculture officials like Heng Chhun Hy in far-flung locales around the world.

But also the Clemson students, faculty and Extension staff who have pitched in and shared in the challenge of diagnosing and solving peoples’ plant and pest problems.

Meg Williamson would tell you that she, herself, was the biggest winner.

And that’s why you may still see her in the CAT Building for a while. Always a team player — even in retirement — Williamson agreed to work a limited schedule until a successor can be named.