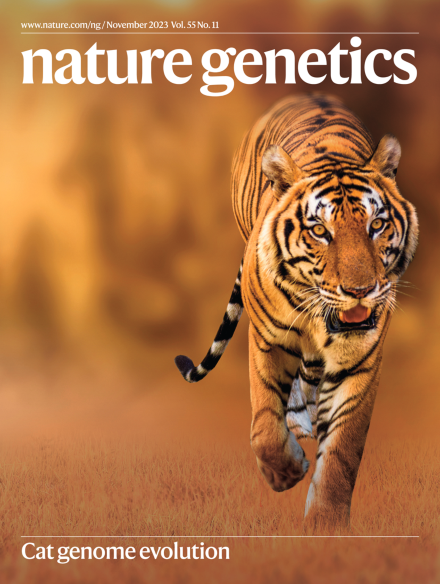

The Bengal tiger was one of five feline lineages compared to gives a comprehensive look at genome sequence structures that could have driven the evolution of distinct cat species. This new reference genome is comparable to the human genome in terms of its completeness, and could be used to for feline veterinary precision health. Denise Allison Coyle/Shutterstock

The tiger doesn’t know it, but a difference deep in its genome sets it apart from other cats.

This big cat preserved a distinct sense of smell thanks to a few chromosomes it uniquely retained over millennia of evolution that other feline species did not.

A study published in the journal Nature Genetics details this finding where scientists from the University of Missouri partnered with Texas A&M University and others to compare, for the first time, nearly gapless cat genomes across multiple species and with humans. This genome map correctly strings together nearly all chromosomes of these felines — from one end to the other without missing segments — to give an animal genetic reference that rivals the human genome.

“This study is a comprehensive look at the genome sequence structures that could be driving cat speciation, the evolutionary process by which populations became distinct species,” said Wes Warren, a Bond Life Sciences Center researcher and MU professor of genomics. “We found distinct differences between how great apes, including humans, and cat sequences evolved in a similar period of time. There were many interesting differences to consider, such as why certain chromosome regions have similar but novel sequence landscapes even across species of cats.”

In tigers, scientists previously identified genes associated with the chemosensory system, perhaps lending them heightened senses of smell key to their survival.

“We see cats have olfactory receptors for sensing smell that are greater than most mammals but, among cats, the tiger stands out with the largest repertoire,” Warren said. “We know tigers have a solitary lifestyle, and that acute sense of smell helps males detect females for mating and lets them avoid the territory of other males to enhance their chances of survival.”

Click here to read more on the MU Decoding Science blog.