By Dr. Mandi Barnard, Research Historian for the Cemetery Project

This post is re-published from the January 2024 newsletter.

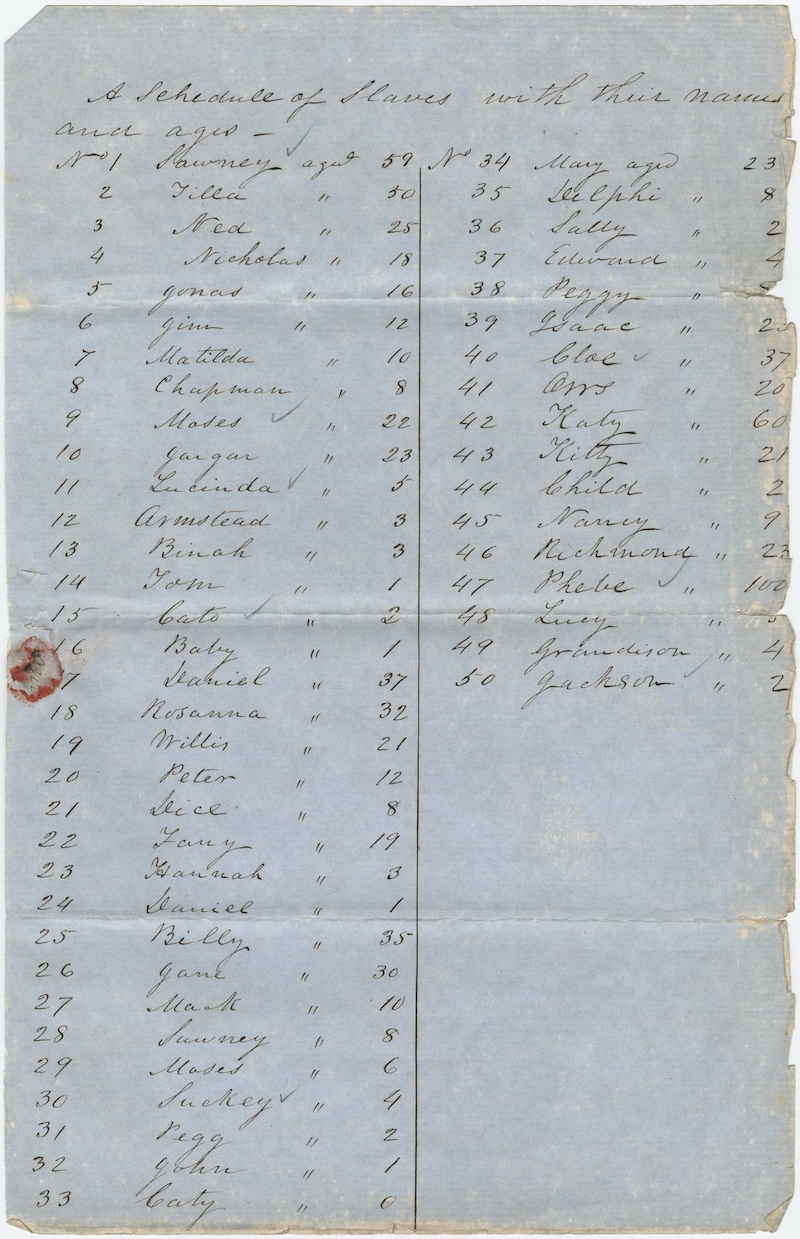

The Cemetery Project works to recognize and recover the history of the African descended persons who lived on this land and were buried in the African American Burial Ground at Cemetery Hill. Over the past year, the Cemetery Team has made tremendous advances in research to recover the names of enslaved persons beyond the 1854 and 1865 inventories at Fort Hill and has gained an understanding of the broader experiences that enslaved people endured. In recognition of Black History Month, the team is producing a two-part history series featuring our latest research.

Through Calhoun family correspondence, plantation ledgers, newspaper accounts, legal documents, and probate records, the team has pieced together more of the history of the enslaved community who lived and labored at Fort Hill. During the 18th century, Lowcountry planters acquired vast lands and large numbers of enslaved persons to cultivate rice, indigo, and sea island cotton. French Huguenot families, such as the Bonneaus, spread their wealth to the upcountry following the Revolutionary War. Samuel Bonneau owned multiple plantations and nearly 100 enslaved people at his death in 1788. His daughter Floride’s husband, John Ewing Colhoun, Sr., accumulated lands and inherited plantations at Santee, Ferry, and Pimlico in the Lowcountry from him. Colhoun began moving enslaved persons from the coast to Twelve Mile Plantation near present day Clemson by 1794. 1

Of the enslaved people Colhoun inherited, Clemson Historic Properties and this team know that a woman named Menimin was from Africa. An 1849 article in the New York Herald mentions this fact, and she was said to be 112 years old. James Scoville, who wrote the article anonymously as “A Traveller,” since he was John C. Calhoun’s private secretary, gave readers a glimpse of the day-to-day life at Fort Hill. He wrote that Menimin had “63 living descendants on this plantation.” The Cemetery team has begun to identify some of their descendants after recovering nine new inventories from John Ewing Colhoun, Sr.’s papers held at UNC Chapel Hill. The team has found that Menimin and her partner Polydore had at least 10 children, including Tom, Katy, and Peggy. These three appear in the John C. Calhoun letters, and in later inventories already known to the project. We are working to reconstruct this family through the generations and hope to recover where Menimin was from in Africa to tie the histories at Fort Hill back to the transatlantic slave trade.2

Though Scoville’s article presented J.C. Calhoun as a benevolent and fair enslaver, relations between enslaved people and their enslavers were not often as harmonious. One dramatic instance of enslaved resistance occurred in 1798. In late summer, five people enslaved by John Ewing Colhoun, Sr., at Twelve Mile, plotted to poison their owners and flee the state. Court records state that Hazard developed the plan, and that Will obtained poison to carry out the plan. Hazard, Sukey, Sue, Jack, and Will did poison the Colhoun family and fled. None of the Colhouns died as a result. The five were captured and tried in court on August 12, 1798. Will was hanged for his role in obtaining the poison. The remaining four were all whipped, branded on the forehead, and had their ears cropped as punishment. In the records for Colhoun’s estate in 1804, all four people appear at Bonneau’s Ferry rice plantation near Charleston. No record exists explaining why the enslaved resisted the Colhouns in this way, but it could be in response to being moved from the coast, or due to the short distance to Cherokee territory, and freedom.3

Floride Bonneau Colhoun, John C. Calhoun’s mother-in-law, inherited the lands and enslaved of her husband, and divided them among her children, including Floride Colhoun Calhoun, who came to live at Fort Hill with her husband John and six children in 1826. Calhoun family letters, and oral history point us to instances of enslaved resistance in the 1830s and 1840s. For instance, Aleck ran away in 1831 after Floride Calhoun threatened to whip him. In 1842 and 1843, siblings Sawney Jr. and Issey both set fires to resist the overseer, and Floride Calhoun, respectively. Furthermore, oral history from descendants of the Calhoun enslaved implies that two enslaved persons also tried to poison Floride Calhoun at Fort Hill during the 1840s.4

Given the undercurrents of tension at Fort Hill the enslaved endured many hardships. Punishments for resistance included imprisonment, whipping, and relocation or sale away from the Calhoun family. In the early 1840s, several enslaved moved between Fort Hill and the Calhoun’s gold mine in Dalhonega, GA. In addition, throughout the 1840s, upwards of twenty enslaved at a time were moved between Fort Hill and John C. Calhoun’s son A.P.’s cotton plantations in Alabama. Issey was among those sent to Alabama as punishment for her arson of the Fort Hill home. Beyond punishment and control, relocation served the Calhouns as an attempt to maximize profit, by increasing labor to improve cotton harvests in Alabama, and to help extract gold. The Calhouns hoped that forcing their enslaved to labor across properties and in difficult conditions would bring financial security. In the end both John C. and A.P. Calhoun died heavily in debt, despite the toil of the enslaved. Next month, the team will discuss what we have learned about the sharecroppers at Fort Hill and the domestic workers, and wage laborers at Clemson College.5

Citations

- October 1794 List of People at Twelve Mile Plantation, Collection 00130, Series 2, Folder 9, John Ewing Colhoun Papers, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

- Joseph A. Scoville, “A Visit to Fort Hill,” The New York Herald (New York, NY), Jul. 26 1849. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83030313/1849-07-26/ed-1/.; John Ewing Colhoun Papers, Collection 00130, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill.

- Account of 1798, Folder 16, John Ewing Colhoun, Sr. Papers, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina. See also W.J. Megginson, African American Life in South Carolina’s Upper Piedmont, (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2022), 26-27.; Will of John Ewing Colhoun, May 30, 1802, in Ancestry.com. South Carolina, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1670-1980 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015.

- Robert Lee Meriwether, William Edwin Hemphill, and Clyde N. Wilson, eds., The Papers of John C. Calhoun, Vol. 1-27 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press for the South Caroliniana Society, 1959-2003), August, 27 and September 1, 1831 v 11 462-463.; April 4, 1843 v 17 136.; December 3, 1845 v 22 314-315.

- R.L. Meriwether, et. al, eds., The Papers of John C. Calhoun, v 12 371, 531-532.; v 16 282-624. v 15 656.; v 21 482-508.; v 23 308.