By Marquise Drayton, Community Engagement Assistant

This post is re-published from the February 2024 newsletter.

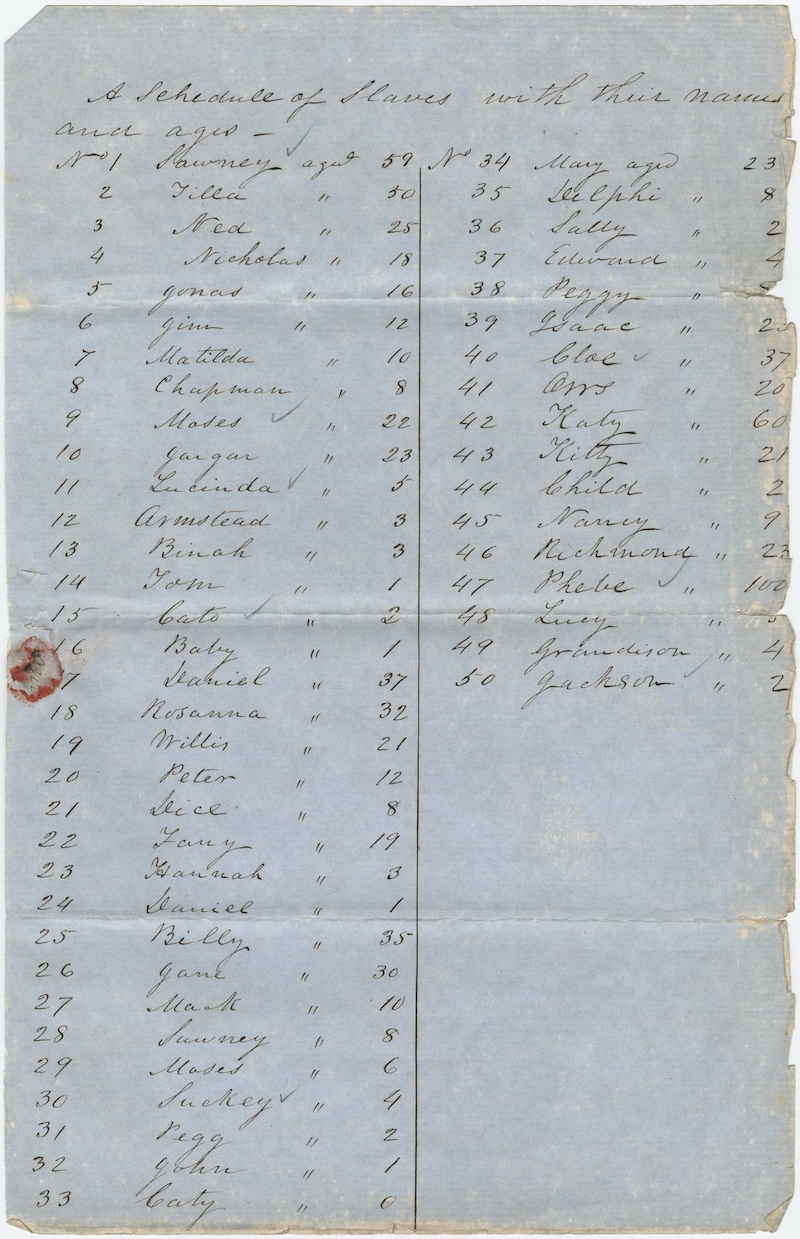

Last month’s edition of the newsletter featured a story that discussed enslaved people at Fort Hill Plantation and their lives with the Calhouns. This month, we will discuss the continuation of African American labor through sharecropping, tenant farming, and domestic workers. Following the Civil War, the formerly enslaved had newfound freedoms as they were no longer considered property. From once-prohibited education provided to Black children to voting rights given to Black men, these newly earned rights came after the divided country fought over “the peculiar institution” of chattel slavery. However, attaining citizenship, freedom, and “40 acres and a mule” was difficult for many formerly enslaved people. Conceptually, it was different to go from being considered commerce as 3/5th a person to becoming a whole person under the court of law. In various instances, the formerly enslaved returned to the plantations where they had labored for a new form of slavery by a different name: sharecropping.¹

The war left the South in financial disarray during the Reconstruction Era as former plantation owners tried to replace the institution of slavery with something similar. The sharecropping system was a 360-deal debtor loophole that the lender (typically, the previous enslavers) kept the borrower (the formerly enslaved) in through credit and repayment of agriculture.² Thomas Green Clemson, a Confederate soldier pardoned by US President Andrew Johnson,³ went into a sharecropping agreement with some former enslaved people of Fort Hill Plantation in 1868.⁴ It included living quarters for the sharecroppers’ families, farming tools, animals for farm labor, access to firewood, rationed bread, and seed from the previous season’s harvest.⁵ However, like the debt owed for previous crops, the profit made by the borrower was heavily in favor of the lender. Duff Green Calhoun, a Confederate veteran and Andrew Pickens Calhoun’s son, used 2 printed contracts provided by the Freedman’s Bureau for freedmen and women that kept them bound to the land they once worked for free, starting in 1866.⁶ Clemson wrote out four contracts for the formerly enslaved, beginning in 1867.⁷ The January 1871-January 1872 contract included many women who agreed to work for Clemson as sharecroppers.⁸

One thing to point out is the lack of transparency of these sharecropping contracts with the indication of illiteracy in marking an “X” between their first and last names.⁹ The contracts were read to them before they signed. But they would not be able to remember all the details. Clemson’s agent’s record book was used if any disputes arose about work/pay, making it even more difficult to ensure they were treated fairly. Understanding how the freedmen and women were not allowed to read during enslavement, there would be no fair way for them to understand what they signed up for.

The work agreements outlined by Thomas Green Clemson not only kept the formerly enslaved in a cycle of debt but checked for behavior while at work that was viewed as rebellious. These rules included “not keeping fire arms or deadly weapons” and “not inviting visitors nor leaving the premises during work hours without written consent.”¹⁰ In instances of theft at Fort Hill, the assumption of “guilty until proven innocent” ruled for those found with stolen goods.¹¹

Manual labor was not limited in the fields either. Domestic work occurred at Fort Hill, from cooking food to rendering childcare.¹² It was more common for women to work in the household—many of whom were formerly enslaved people.¹³

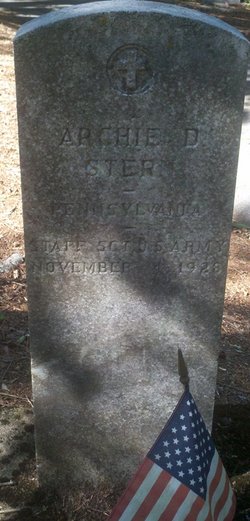

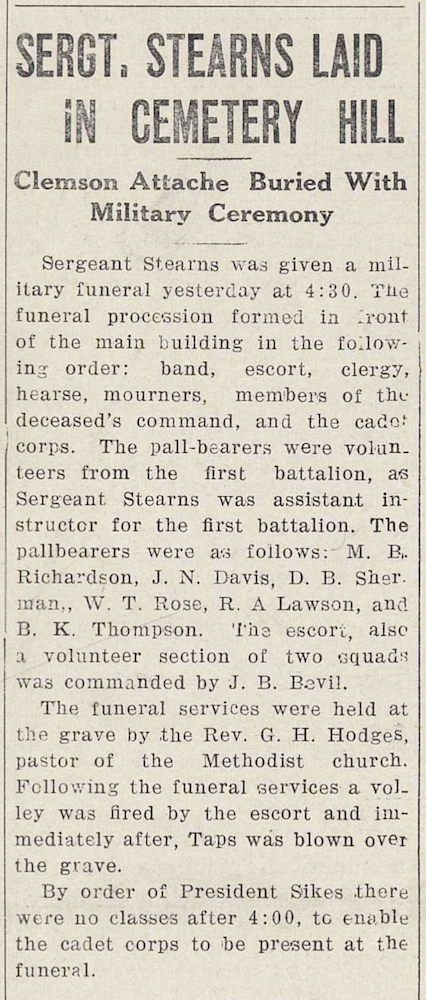

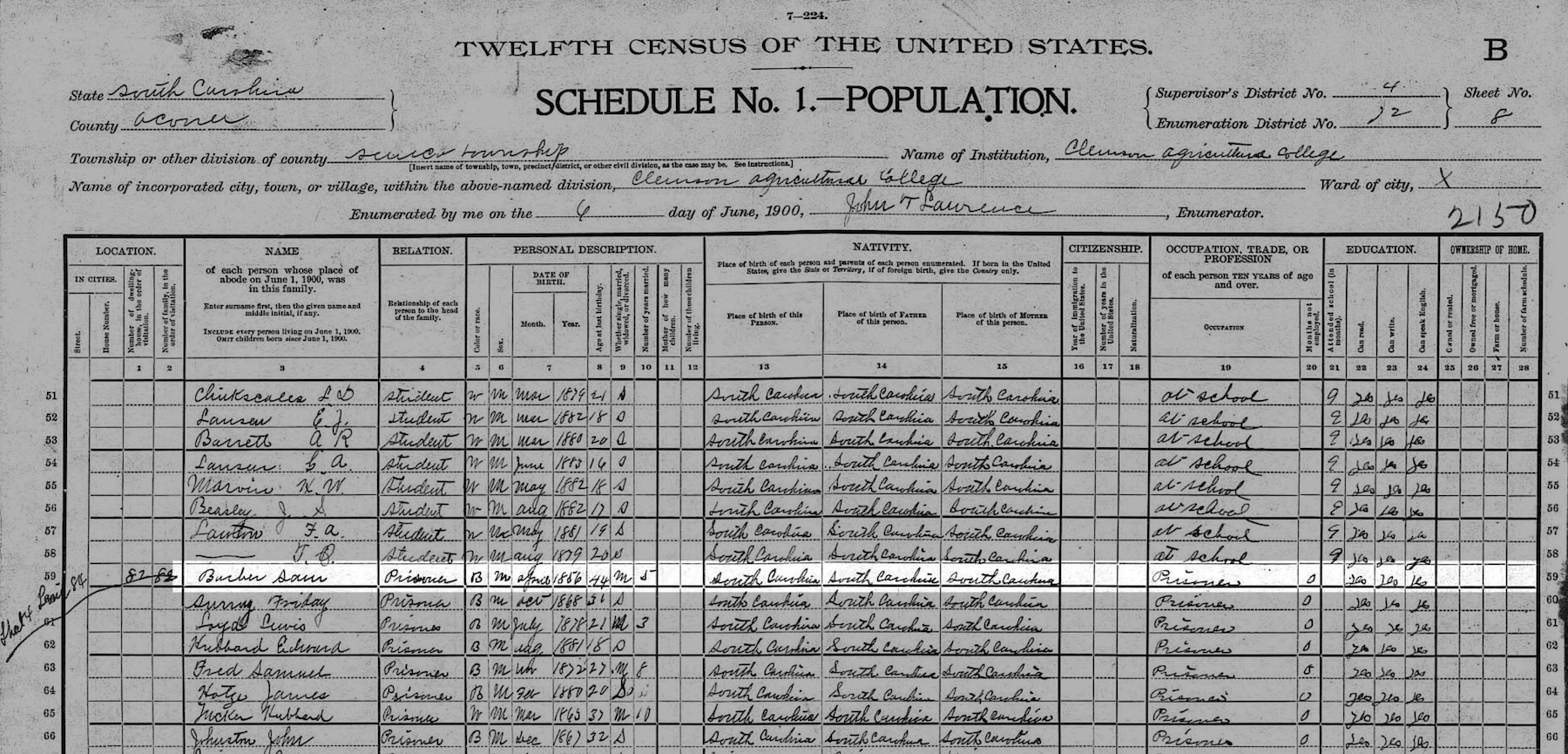

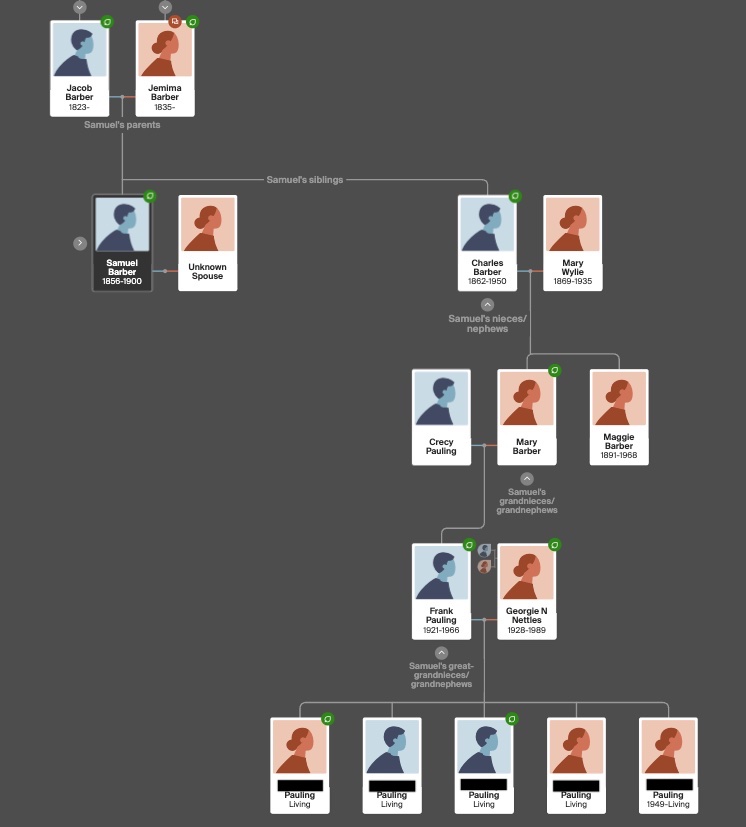

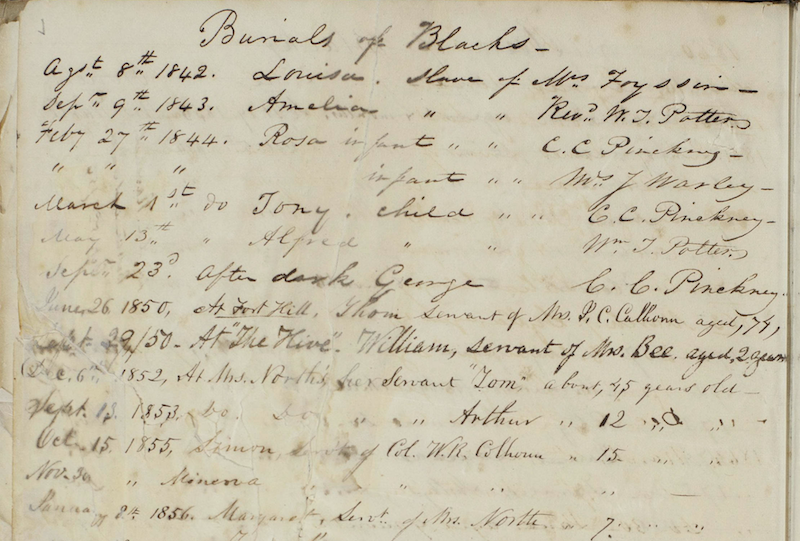

For decades, both free and enslaved Black laborers worked the land in which we see today. As the college was established in 1889, convicted laborers followed from 1890 to 1915, helping to build everything, including four buildings for Clemson College that are still standing. What followed them were wage workers in the early 20th century and their families. Enslaved persons and other laborers who work on the land may be buried in the cemetery.

During Black History Month 2024, we ask that you consider the intergenerational nature of the project with how African Americans have impacted the land grant institution from the antebellum era to contemporary times.

Citations

1) Tetreau, Jared. 2023. “Sharecropping: Slavery Rerouted.” PBS.Org. WGBH Educational Foundation. August 16, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/harvest-sharecropping-slavery-rerouted/.

2) Ibid.

3) Caroline M. Ross on behalf of Fort Hill. “Fort Hill-Parlor.” Clio: Your Guide to History. July 30, 2020. https://theclio.com/entry/104472.

4) “Articles of agreement between Thomas G. Clemson and freedmen and women, 1868 January 1” (1868). Thomas Green Clemson Papers, Mss 2. 1134.

https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1134.

5) Ibid.

6) “The Reconstruction Era” in History of the African American Burial Ground. Woodland Cemetery Historic Preservation. https://www.clemson.edu/about/history/woodland-cemetery/histories/burial-ground.html.

7) Ibid.

8) “Articles of agreement between Thomas G. Clemson and freedmen and women, 1871 January 1” (1871). Thomas Green Clemson Papers, Mss 2. 1159.

https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1159.

9) “Articles of agreement between Thomas G. Clemson and freedmen and women, 1867” (1867). Thomas Green Clemson Papers, Mss 2. 1133.

https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1133.

10) “Articles of agreement between Thomas G. Clemson and freedmen and women, 1867” (1867). Thomas Green Clemson Papers, Mss 2. 1133.

https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1133.

11) “Articles of agreement between Thomas G. Clemson and freedmen and women, 1871 January 1” (1871). Thomas Green Clemson Papers, Mss 2. 1159.

https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1159.

12) Cassettes 1 & 2 (Viola Williams), Mss 282, Black Heritage in the Upper Piedmont of South Carolina Project Collection, Special Collections, Clemson University Libraries, Clemson, SC.

13) Cassette 1 (Lucille Vance/Yolanda Harrell), Mss 282, Black Heritage in the Upper Piedmont of South Carolina Project Collection, Special Collections, Clemson University Libraries, Clemson, SC.