Recognizing that the effective evaluation of faculty teaching requires a multifaceted approach, Clemson University adopted a model that considers not only the course evaluation forms completed by students but also two additional metrics of teaching effectiveness. Besides addressing instances of over-reliance on student evaluations, the idea behind these changes is that a more diverse set of metrics is less likely to be affected by the same variables, thus providing faculty a fair opportunity to showcase (and get credit for) everything they do to advance the educational mission of the institution.

Assembling a Teaching Portfolio

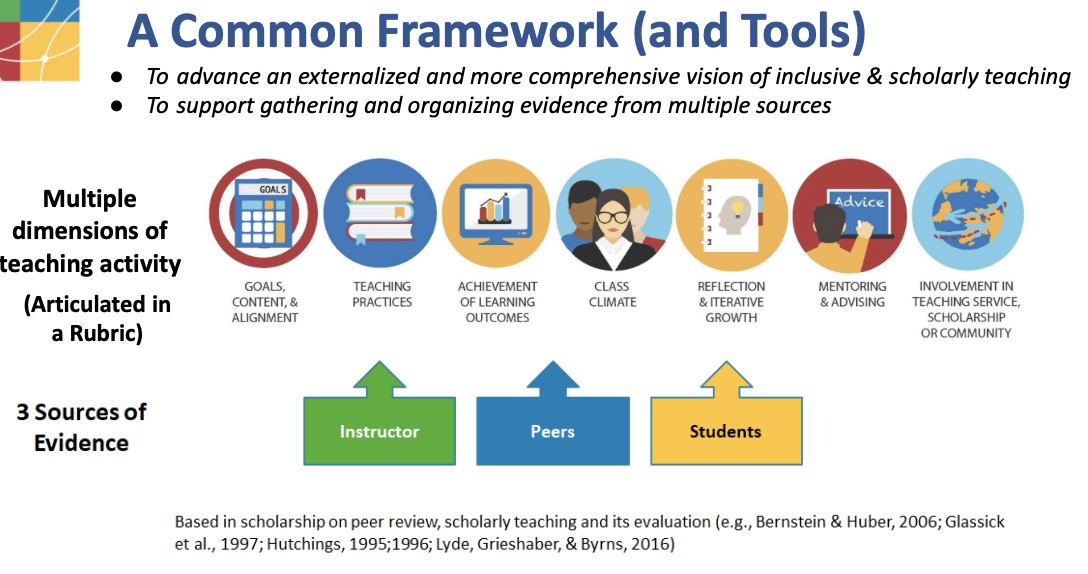

In order to comply with these requirements, the faculty manual lists a number of options in terms of materials to be used as additional metrics to document teaching effectiveness, including evidence-based measurements of student learning that meet defined student learning outcomes, evaluation (by peers and/or administrators) of course materials, learning objectives, and examinations, in-class visitation by peers and/or administrators, a statement by the faculty member describing the faculty member’s methods, exit interview/surveys with current graduates/alumni, and any additional criteria as appropriate for the discipline and degree level of the students. The latter category is especially important, as it allows faculty to discuss information from course materials (syllabus, lectures, assignments, tests, examples of student work, Canvas page, communications, etc.), profile of students (enrollment, the type of student taking the class: concentrators, first-year students, non-specialists, graduate students, etc.), documentation of innovative teaching approaches and special efforts invested to improve learning outcomes, faculty development efforts (course design, development of new courses, flipped courses, mentoring of other teachers, etc), inclusion of previous feedback, inclusion of course modules that support the goals of Clemson Elevate (integrating activities aimed at highlighting inclusive excellence, global engagement, service and/or experiential learning, etc.) or a course audit for accessibility (Clemson OnLine). More generally speaking, these materials can be broadly classified into three buckets, containing information from the students (surveys), information from the faculty member (teaching statement), and information from peers (formative feedback). In all cases, the objective is for faculty to provide not only the information supporting their activities but also the context to interpret such information, from the lens of their own professional development path.

Adapting the Faculty Handbooks

Considering that these requirements have been in place since Fall 2023, it is critically important to emphasize the need to adapt the department’s faculty handbooks, so the teaching components of faculty’s annual evaluations consider the additional metrics. It is also important to state that no single quantifier from the course evaluation forms completed by students (including individual questions or combined scores from selected questions) may substitute for a wide-ranging review of the responses (Chapter V§E2e).

One source of information that could help departments is the CRTL (U. Michigan), that also implemented a multidimensional approach to assess teaching. In this case, they specifically list instructional delivery, course planning, grading, course management, oversight of independent studies (honors theses, prelims, dissertations, etc), support for student internships, experiential learning, service learning, department and curricular work, advising/mentoring, and professional development/innovation around teaching. Departments can also consult recommendations from the TEVal Project, that also follow the model of the three buckets (information related to peer review, student evaluations, and self reflection). A common theme in the project is that regardless of the institution (KU, CU, or UMass), the evaluation of teaching is based on multiple dimensions, with the caveat that not every institution uses every metric and that the weight assigned for each dimension could also vary.

It is also important to mention that several reports have pointed to the relevance of Behavioral Anchored Rating Scales (BARS) for the evaluation of teaching effectiveness. In this case, the performance levels are defined in terms of expectations (Does Not Meet / Needs Improvement / Meets / Exceeds / Outstanding) for a set of tasks. As a general example, the following article (Coursera) describes an example of how BARS can be used to provide formative feedback linked to specific behaviors representing anchor points for the dimensions evaluated, rather than using generic descriptors to rate employees from poor to excellent. It is also important to mention that BARS are being increasingly used to assess teaching effectiveness, leading to increased buy-in, and potentially impacting student’s performance.

Additional Resources

- Assessing Teaching Effectiveness, University of Buffalo

- Documenting Teaching Effectiveness, UC Berkeley

- Methods to evaluate your teaching, University of Oxford

- Behavior Anchor Rating Scales (BARS), Purdue University

- Examples of BARS in academic settings

Want to know more?

If you have any questions regarding this post, please contact:

If you have any questions regarding this post, please contact:

DR. CARLOS D. GARCIA

Faculty Fellow, Best Practices in Faculty Reviews

Office of Faculty Advancement

cdgarci@clemson.edu

Please use this form to provide feedback, propose stories, or nominate a colleague to be featured (including self-nominations).