It’s the time of year to be on the lookout for stink bugs in corn in South Carolina. Several species can cause damage, with the brown stink bug, Euschistus servus, and southern green stink bug, Nezara viridula, being the most common. While damage at the seedling stage can occur, the most common injury occurs when stink bugs feed from V14-VT. Which leads to crooked or banana shaped ears. We outline here information on stink bug biology, damage, and management.

Overview and identification

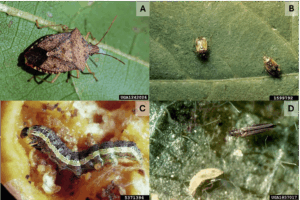

Stink bugs are shield-shaped insects, which have a similar appearance across species. As the name suggests, the brown stink bug is dark brown in color. There is a beneficial stink bug species called spined soldier bug that may be confused with brown stink bugs, but is distinguished by the presence of pointed and sharp shoulders (i.e. pronotum), which are absent on the brown stink bug. Immature or nymphal brown stink bugs are light green in color with a brown patch on their abdomen. Southern green stink bugs are slightly larger than brown stink bugs and green in color. The nymph of southern green stink bugs has a series of pink, white, and black spots on their abdomen, which can be used to distinguish them from other species. Other species such as the brown marmorated stink bug, green stink bug, and rice stink bug can be common in South Carolina, but are not common pests of corn.

Left: adult brown stink bug. Image credit: Gerald Holmes, Strawberry Center, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, Bugwood.org. Right: fourth instar brown stink bug nymph. Image credit: Herb Pilcher, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org

Left: Adult southern green stink bug; note the presence of tachinid fly eggs. Right: fourth instar southern green stink bug nymph. Image credits: Russ Ottens, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org.

Damage to corn

Field corn is susceptible to injury during three key stages of field corn development: 1) emergence (VE) – six-leaf stage (V6), 2) two weeks prior to tasselling (VT) during the earliest stages of ear development, and 3) the first two reproductive stages of development (R1 and R2). During the early vegetative stages (i.e. VE-V6), stink bugs feed directly on the growth point of young plants, which can lead to stunted plants, tillers, leaf holes, deformities, or plant death in severe cases. Prior to tasseling, feeding leads to a characteristically crooked or “banana-shaped” ear, which limits overall yield potential and can expose the ear to secondary pests and pathogens. It is important to note that during these stages, the ear is not yet visible, but stink bugs can use their mouthparts to penetrate into the plant and find the developing ear to feed on. After pollination, feeding on kernels has limited potential to directly impact yield but can introduce grain quality issues in the form of fungi and mycotoxin contamination if bugs are at a high enough density.

Early vegetative injury from stink bug feeding, with severely stunted plants. Image credit: Tim Bryant, Clemson University.

Banana-shaped ears as a result of stink bug feeding during late vegetative stages prior to tasseling. Image credit: Tim Bryant, Clemson University.

Discolored kernels and fungal growth as a result of stink bug feeding during early reproductive stages of corn development. Image credit: Tim Bryant, Clemson University.

Sampling and management

During early vegetative stages, fields that are planted into heavy cover crop residue can potentially be at higher risk for large populations and injury. Proper seed slot closure can be affected by this heavy cover and expose more sensitive portions of the plant to feeding, increasing injury potential. Fields that were planted with soybeans in the previous season can also be at a higher risk for early-season infestations. As wheat matures and dries down, the interface of wheat and corn is at high risk for stink bug infestations. Wheat is an excellent early-season host for stink bugs, which can easily move into nearby corn during wheat harvest. Wheat harvest often coincides with the later vegetative stages of corn development, which are susceptible to stink bug injury.

For early vegetative infestations, insecticidal seed treatments, which are applied almost universally to commercial corn seed, can provide some protection from early season injury. Generally, fields with a history of stink bug pressure or at risk of injury from soil pests may benefit from increased seed treatment rates. Additionally, foliar insecticides can effectively manage stink bugs throughout the season, but it is critical to scout and only apply an insecticide at the economic threshold level for the given growth stage. The economic threshold is 1 bug per 10 plants from V1 to V6, 1 per 4 plants from V12-VT, and 1 per 2 plants at R1 and R2. The two most important considerations for applying an insecticide are achieving good coverage and timing the application properly. Ensuring canopy penetration is especially critical during the later stages of corn development. Bifenthrin is generally the most effective material to target brown stink bugs specifically. Applying an insecticide only at the economic threshold level will also preserve naturally occurring biological control agents in the field that broad-spectrum insecticides would otherwise kill.

For more detailed biology and management information on brown stink bugs in field corn, see this Land-Grant Press article and this scouting guide for stink bugs in southeastern corn.