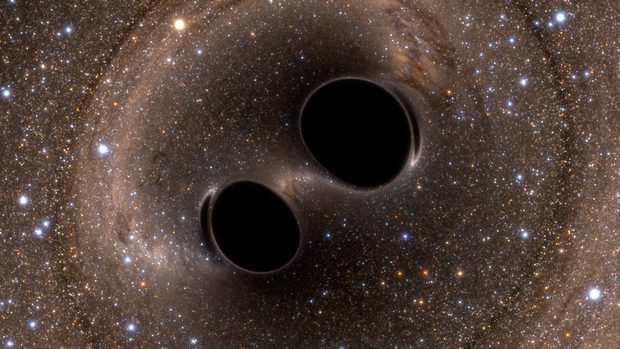

Every galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center. But according to astrophysicists, they sometimes they feature a binary system, or two supermassive back holes orbiting each other. Black holes act as cosmic vacuum cleaners, with a mass a million times that of our Sun, formed when the core of a massive star collapses on itself. They are regions in space where gravity is so strong that not even light can escape, and scientists use them to help study how gravity works and how galaxies form. By studying the frequency of binary supermassive black holes, researchers can better understand what happens to galaxies when they merge.

Binary black holes emit gravitational waves, ripples in space-time that travel at light speed, stretching and squeezing space as they pass. Pulsar timing arrays, which analyze the radio signals from rapidly spinning pulsars, detect anomalies caused by these waves. While these arrays can pick up the combined signal from binary black holes over the past 9 billion years, they are not yet sensitive enough to detect individual systems within a single galaxy. Since even the most powerful telescopes cannot directly image these binaries, astronomers rely on indirect methods to determine their presence in galactic centers.

Astronomers use indirect methods to identify binary black holes, including searching for periodic signals from active galactic nuclei: high-energy galaxy centers. These nuclei emit intense radiation due to accretion, where the black hole pulls in surrounding gas, causing it to heat up and glow in optical, ultraviolet, and X-ray light. Some active galactic nuclei also launch jets of particles moving near light speed, appearing exceptionally bright when aligned with Earth. A periodic brightening and fading of light from these nuclei could indicate the presence of two supermassive black holes orbiting each other, signaling a potential binary system.

A new study by Marco Ajello, Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Clemson University, and Jonathan Zrake, Assistant Professor of Physics at Clemson University, analyzed over a century of astronomical data to investigate whether the active galactic nucleus PG 1553+153 harbors a binary supermassive black hole. The galaxy’s light brightens and dims every 2.2 years, suggesting a binary system, but other explanations like wobbly jets had to be ruled out. Simulations showed that if a binary existed, dense gas clumps should orbit the black holes every 10 to 20 years. Using the DASCH database, which digitized photographic plates dating back to 1900, the team identified a 20-year pattern, supporting the binary black hole theory. Their findings also indicated that the two black holes have a 2.5:1 mass ratio and a nearly circular orbit. However, final confirmation may require future gravitational wave detections from pulsar timing arrays.

Written by David Brandin

Adapted from Some black holes at the centers of galaxies have a buddy − but detecting these binary pairs isn’t easy | Clemson News