Biochar and Importance in SC

Forests cover about two-thirds of South Carolina’s land area and provide not only timber but also a vast source of renewable biomass- the leftover wood from thinning, logging, or forest management activities. Much of this material is currently underused, often left to decompose or burned in piles, which can increase wildfire risks and release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Biochar can store carbon for decades, improve soil quality, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This research study aimed to identify the optimal locations for biochar production facilities in South Carolina, maximizing environmental benefits while minimizing transportation and production costs.

Biochar is produced through a process called pyrolysis, which transforms wood waste into a stable form of carbon rather than allowing it to decay and release carbon dioxide. Once added to soil, biochar enhances water retention, improves soil fertility, and increases nutrient availability, thereby supporting the growth of crops, particularly in sandy or degraded soils typical in South Carolina. Biochar also has environmental and economic benefits: a) Capture and store carbon, b) Reduce wildfire risk by converting excess forest fuel into a useful product, c) Create new economic opportunities for rural areas and forest industries, and d) Support agriculture by enhancing soil health and water efficiency.

Biochar Market in the South

The biochar market in the southern United States is gaining traction, driven by the region’s abundant woody and agricultural biomass, a favorable environment for soil-amendment use, and growing interest in both regenerative agriculture and carbon-sequestration solutions. Recent reports indicate that the U.S. South already dominates the national biochar market, mainly due to its large forest and agricultural sectors, which drive feedstock availability and end-use demand. Technology and production models are evolving from small experimental units to more established mid-scale facilities aligned with forest-residue utilization, and policy interest is increasing through federal and state programs that recognize biochar’s role in environmentally smart forestry and agriculture. However, the market remains nascent with challenges including inconsistent quality standards, limited awareness among producers and landowners, and uncertain economics for distributed mid-scale operations. Addressing these barriers is crucial for the region to fully scale biochar production, link forestry residues with soil health markets, and achieve both environmental and economic benefits.

Study Approach

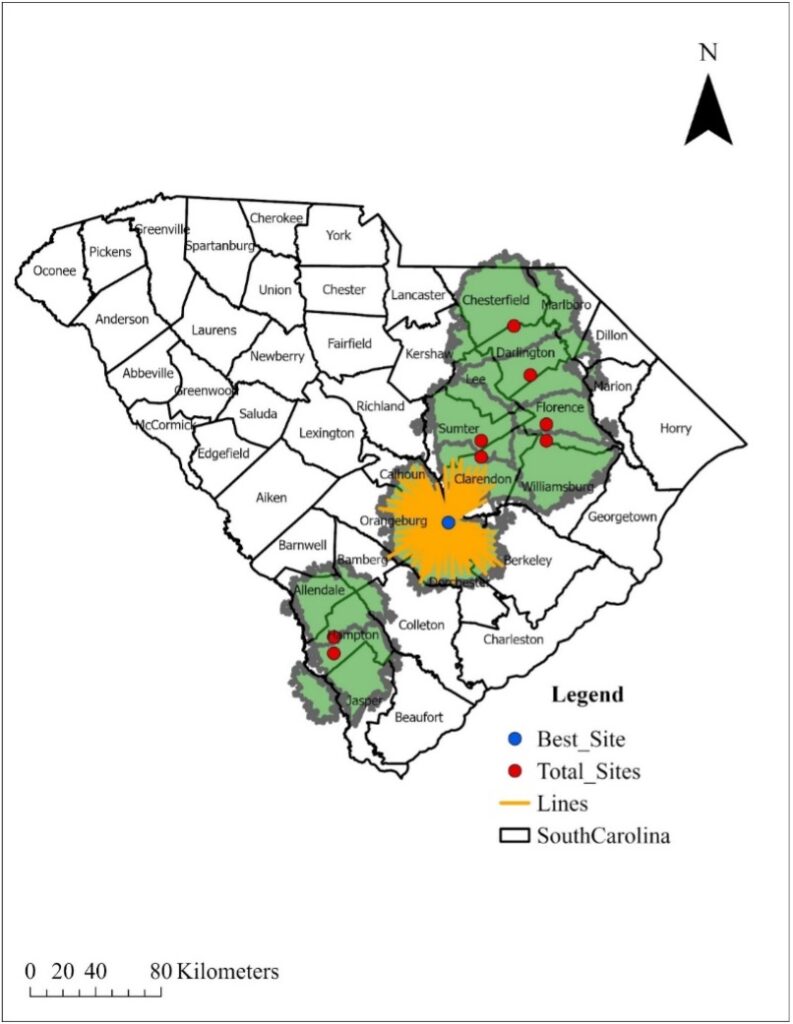

Using a spatial modeling framework, we identified nine optimal locations across South Carolina for biochar production facilities (Figure 1). These sites were determined through a multi-criteria decision analysis that incorporated forest biomass availability, slope, soil characteristics, proximity to croplands, wildfire occurrence, and accessibility to mills and transportation routes. Areas unsuitable for development such as water bodies, urban lands, or federally owned forests were excluded from analysis.

Results – Potential Biochar Locations in SC

The study identified Orangeburg, Chesterfield, Hampton, Darlington, Florence, Williamsburg, Sumter, and Clarendon Counties as the most suitable areas for biochar production facilities in South Carolina. These locations combine abundant forest biomass resources with proximity to existing wood mills and major transportation routes, making them ideal for medium-scale, distributed biochar operations. Across all nine priority sites, researchers estimated an annual biomass availability of roughly 71,000 tons, capable of producing approximately 14,200 tons of biochar per year. Orangeburg County showed the highest potential output, followed closely by Chesterfield and Hampton, indicating that these regions could serve as central hubs in a future biochar production network.

Transportation modeling revealed favorable logistics and manageable costs. Average hauling distances between biomass sources and proposed facilities were 30 to 35 kilometers, supported by well-connected road networks. The average transportation cost of $12–13 per ton accounted for only about 13% of total delivery expenses, while processing and chipping averaged $77 per ton. These findings suggest that biochar production could be economically feasible, particularly when the feedstock comes from forest thinning, restoration projects, or mill residues that currently hold little or no market value. Strategic siting of facilities near these resource flows could significantly lower costs while improving the efficiency of biomass utilization.

Spatial mapping also showed a notable overlap between high-biomass forestlands and wildfire-prone areas, emphasizing the dual benefits of this approach. Establishing biochar facilities in these zones could help reduce hazardous fuel loads while converting waste material into a valuable soil amendment. South Carolina’s forests, covering about 67% of the state’s land area (5.2 million hectares), represent an underused resource for sustainable biochar production. Most forests are privately owned, dominated by pine plantations and mixed hardwood stands that generate substantial residues during thinning or harvesting. Converting this biomass into biochar aligns with broader environmental mitigation and sustainable land management goals, offering both ecological and economic value.

Biochar’s long-term benefits make it an attractive option for both forestry and agriculture. It locks away carbon for decades, improves soil structure and water retention, and can enhance crop productivity, particularly in South Carolina’s sandy, nutrient-poor soils. Counties such as Orangeburg, Chesterfield, and Hampton are particularly well-positioned to connect forestry feedstocks with nearby agricultural lands that could utilize biochar to enhance soil health. From a policy and economic standpoint, the development of decentralized, mid-scale biochar facilities could generate new opportunities in rural communities, including participation in carbon credit schemes, job creation, and market diversification. Furthermore, deploying mobile pyrolysis units in remote areas could expand access to this technology, reduce transport needs, and support local forest restoration and wildfire prevention efforts, making biochar a cornerstone of sustainable resource management across the state.

Reference

Sharma, S., & Khanal, P. (2026). Mapping biochar potential in South Carolina: A spatial strategy for climate mitigation and soil restoration. Biomass and Bioenergy, 205, 108532.

Author

Puskar Khanal, Cooperative Extension, Forestry and Wildlife Specialist

This information is supplied with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no endorsement of brand names or registered trademarks by the Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service is implied, nor is any discrimination intended by the exclusion of products or manufacturers not named. All recommendations are for South Carolina conditions and may not apply to other areas.

Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service offers its programs to people of all ages, regardless of race, color, gender, religion, national origin, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital or family status and is an equal opportunity employer.